by Amm Admin | Jul 23, 2020 | Blog

Reporting: Julian Jacobs

Editing: Francis Mdlongwa

Makhanda (Grahamstown), South Africa — Highway Africa (HA), the continent’s biggest and oldest conference series run by Rhodes University, has launched a series of high-level webinars that seek practical solutions to challenges that face African media and journalism in the era of Covid-19 and how to exploit emerging opportunities.

The first of these webinars was held on 30 June and brought together some of Africa’s leading media owners, editors and commentators, who shared their insights and experiences on ‘’The Future of Journalism and Media in Africa’’ during the 90-minute online seminar. The series is dubbed ‘’Our Futures, Our New Normals’’.

Covid-19, a novel virus that erupted last December, has killed hundreds of thousands of people across the world and decimated businesses and left millions of people jobless as governments shut their economies to try to arrest the pandemic’s spread.

Many media companies in Africa and across the world have folded because of the pandemic, throwing thousands of journalists out of their jobs in the worst health pandemic to hit the globe since the Spanish flu that killed millions in 1918.

In an ironic development, Covid-19 has also enabled some leading news firms such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times of London to dramatically increase the number of their paying readers and thus increase their revenue as audiences frantically sought trusted news content on the pandemic. These newspapers had long placed their journalism under paywalls, which force readers to pay money to access news content hidden behind online gardens.

Sandra Gordon, a veteran magazine publisher and managing director of Stone Soup, a media group in South Africa, spoke at the webinar to urge African media houses to be creative and courageous and to collaborate to survive the disruption of Covid-19.

Gordon shared the high table of speakers with Styli Charalambous, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Daily Maverick, one of South Africa’s digital-only newspapers; Dr Roukaya Kasenally, an Associate Professor in Media at the University of Mauritius and the CEO of the pan-African Africa Media Initiative; and Julie Masiga, a leading media editor based in Kenya who has worked across Eastern Africa and is now an editor for The Conversation, an online opinion platform mostly for African scholars.

The webinar, staged with the support of the School of Journalism and Media Studies at Rhodes University, was moderated by Professor Anthea Garman, the Acting Head of the School, and Francis Mdlongwa, Director of the Sol Plaatje Institute for Media Leadership and the acting director of Highway Africa.

A grim picture for print media

Gordon painted a grim picture of the state of print magazines in South Africa, where many magazines have closed their doors recently.

She did, however, highlight that there could be a way out for those wanting to buy into the magazine industry. “You have to have a modern business model, you need to change the way you do business, adopt new technologies, become innovative and involve yourself in e-magazines, events…and still maintain the ideals of the Fourth Estate to allow for freedom of expression and to protect it,” she said.

Masiga said the media in Eastern and Central Africa was already facing financial upheaval even before Covid-19, with many media houses closing down because of being deserted by audiences and advertisers, the latter the single biggest revenue earner for media.

Covid-19 had thus accelerated the closure of some media firms. “One way that could help is for media houses to digitize and tap into this market, especially as audiences make use of cellular phones to access news,” she noted.

Masiga said the move from traditional media to digital had created an environment where professional journalists were competing with increasing numbers of content creators, including audiences, and underscored the importance of journalists differentiating themselves by being truthful and accurate in an environment that had spawned misinformation and false news.

Charalambous reflected on his newspaper’s journey over the last decade and indicated that at first it was difficult to break even financially until they figured out a way to get the readers involved.

He said that over the last two years the Daily Maverick had launched a bold readers’ membership programme. Under this innovative arrangement, the Daily Maverick took steps to listen to its audiences’ news needs and wants and then provided them with cutting-edge investigative journalism.

“We also embraced new skills in our organisation such as people working on new business products, technology, innovation and marketing. We needed to sustain this going forward and we even employed community managers and membership managers, something we would not have done a few years back,” Charalambous said.

Kasenally echoed the sentiments of the other panellists and warned that “unless media houses do actual market analysis and make use of market intelligence data to navigate and plan the way forward, then the media in some areas in Africa will become obsolete.”

She lamented the trend of media houses merely going digital and creating an even bigger digital divide between those who have online access and those who did not. “There is a culture (in Africa generally) of not wanting to pay for (news) content and media houses need to be aware of this to change this culture,” she said, referring to paywalls, which propped up the financial fortunes of those media houses which produce unique, compelling and credible news content.

Kasenally called for the establishment of a Media Africa Solidarity Fund to help struggling media houses across the African continent to ride the Covid-19 storm. “Media houses must take up this opportunity to do things differently now, during the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as create and develop (news) content that is unique and appealing to audiences, readers, and listeners.”

Highway Africa, established more than two decades ago, is Africa’s oldest conference series which has usually run annual conferences that are focused on developments of the continent’s journalism and media and are attended by hundreds of African journalists.

There will be no conference in 2020 because of Covid-19, but a Highway Africa summit conference is planned for June 2021.

by Amm Admin | Jun 2, 2020 | Blog

byALICE DE SOUZA May 28, 2020 in COVID-19 REPORTING

Brazil has become a new epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic, reaching 20,000 deaths on May 21. The official numbers may be the tip of the iceberg as a study conducted by the University of São Paulo shows the country could have 14 times more infected cases than the number reported. There has also been exponential growth in hospitalizations and deaths from Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), when compared to the previous 10 years. Deaths at home have also increased by 14.6% compared to 2019.

For Brazilian journalists, this created the challenge of telling the stories behind the numbers and of using journalism to help family and friends memorialize their loved ones when funerals and burials are limited by the virus.

Data journalist Judite Cypreste spent two weeks producing a map by municipality of COVID-19 cases in Brazil, but the work made her feel uneasy. “We needed to do a story where the numbers were the starting point and include the stories, the human [side of it],” she said.

Cypreste’s concern gave rise to the special report “Números Subestimados” [Underestimated Numbers], co-produced with journalist Luís Adorno and published on April 30. “This story shows that people are not numbers. It is important to give a face to the data to say that the pandemic is real, that it is happening, that the victims may be your neighbor, a relative. It brings the narrative closer to the readers,” said Cypreste.

Since April 4, Folha de S. Paulo, Brazil’s largest newspaper, has published the special “Histórias de vítimas do novo coronavírus” [Stories of victims of the new coronavirus], which lists obituaries by week. The G1 portal published the page “As vítimas da COVID-19” [The victims of COVID-19], a memorial that compiles stories about the lives of some of the people who died from complications of the new coronavirus. Other news organizations have followed, creating special coverage of the people who have died in the pandemic.

Inumeráveis

Telling the stories hidden under the statistics was also the driving force behind the launching of the collaborative memorial Inumeráveis [Innumerable]. Under the motto “no one likes to be a number, people deserve to exist in prose,” the initiative went live on April 30, inspired by artist Edson Pavoni and social entrepreneur Rogério Oliveira.

The stories for Inumeráveis come together through the efforts of volunteer journalists. “The numbers keep growing, and we must not forget that they mean people, who had a life of love, sadness, happiness, and who left friends and family. The memorial is a portrait, albeit a small one, of this anxiety of not knowing these people,” explained journalist Alana Risso, one of the project coordinators.

Faced with the speed of the pandemic, a group of eight individuals brought the idea to life in three weeks, and since launch, journalists and journalism students can volunteer to collaborate. “We know that no newsroom has enough staff to keep track of the cases, especially considering Brazil’s inequality, where so many places — the news deserts — don’t have a media outlet. So, the idea is to mobilize journalists from all over the country to locate the stories and remember the people who died,” said Rizzo.

Journalists can collaborate with Inumeráveis in three ways. They can report on a story and publish it on the website, upload an obituary that has been published by another media organization or review texts and transcribe audio sent by friends and relatives of COVID-19 victims. The website has a form to upload the stories, as well as contact information for collaborators. Everything that is published is fact-checked, following the initiative’s methodology. According to Rizzo, there are plans to transform the memorial into a print product in the future.

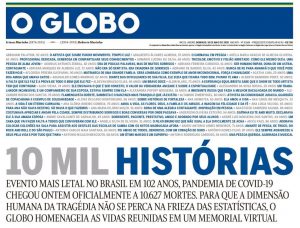

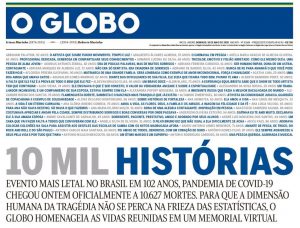

The day after Brazil passed the mark of 10,000 deaths by COVID-19, and two weeks before The New York Times’ front page project, newspaper O Globo devoted its entire front page to a long list of names, ages and phrases about the lives of some of the victims of the new coronavirus in partnership with the Inumeráveis memorial. Among the nearly 140 names, the headline read:

The special report, dedicated to mourning and honoring those who have died had two additional pages. In the text, journalists Rennan Setti and Gabriel Cariello explain that even when reduced to a number, the coronavirus’ lethality is enormous.

Memorial Corona Brasil

Another collaborative initiative is Memorial Corona Brasil, created by the Support Network for the Families of Fatal Victims of COVID-19, a group of 60 organizations in solidarity with the families of victims of the pandemic. Journalists can collaborate by editing the stories on the Facebook page according to the methodology developed by the network, helping comfort families or participating in a working group alongside historians and social scientists to think about ways to memorialize the pandemic.

“There is an experience of redefining how we mourn as we are trying to deal with it very strictly. Society is experiencing mourning and people are afraid. At this time, many people want to connect on social media to pay homage to the memory of those who have passed. Our work is a way to help with the ritual of saying goodbye,” explained historian Danilo César, one of the creators of the network. The network also compiles stories produced by other journalists and conducts their own research to create other forms of pandemic memory.

Source: https://ijnet.org/en/story/names-behind-numbers-honoring-covid-19-deaths-brazil

by Amm Admin | Apr 20, 2020 | Blog, Uncategorized

The coronavirus, which causes the disease known as Covid-19, has killed thousands of people across the world and upended the lives and work of billions of others still lucky to count themselves alive. Never before in the past century has a disease wrought so much human havoc and suffering and precipitated an unprecedented global health pandemic of unimaginable proportions.

Governments across the globe have responded by imposing emergency rule and nationwide ‘lockdowns’, which force people to stay in their homes in a bid to slow down the spread of the virus. Millions of people, especially those in the poor developing nations, have found themselves not only facing the threat of this killer virus but severe shortages of food and other life-saving essentials.

Doctors and other health workers in the most countries affected have had to contend with trying to save the lives of an unending stream of critically ill people without adequate medical ventilators that are meant to help the sick to breathe easier nor an antidote for this novel virus.

The lack of medical protective equipment for the health workers is endangering their lives, as well as the lives of their family members and of all those they are in contact with because the novel coronavirus is highly contagious. Indeed, dozens of doctors and other medical personnel have already died in this pandemic, which is reported to have started in China in December 2019 and has fanned like wildfire to more than 180 countries within three short months.

The role of journalists in covering this pandemic

Journalists across the world have played a crucial role in informing and educating the public about Covid-19, its known symptoms and preventative measures that people can take, where citizens can access medical care and food, and what their governments are doing to stem the disease’s tide.

In many countries, stretching from South Africa to China, governments have enacted legislation that prohibits members of the public and journalists from spreading ‘fake or false news’ on the disease, forcing most journalists to rely only on the official government accounts of the disease’s spread and horrific death toll.

It is in this environment that investigative journalists could and should make a positive intervention through their work of surveillance and of scrupulously holding to account all those in power and of others who are involved in efforts to mitigate the spread of this disease. The journalists should and must continue to shine a torch on the actions of at times overzealous officials, who may seek to curtail the basic human rights of citizens or exceed their powers, or of other people and officials who may seek to profit from this crisis.

Highway Africa (HA), working in collaboration with the Partnership for Social Accountability (PSA) Alliance and its partners that include the Public Service Accountability Monitor (PSAM) headquartered at Rhodes University in South Africa, has adapted PSAM guidelines which investigative journalists may find useful in doing their work in this period of anxiety, fear and even confusion among many people.

The guidelines below are just guidelines, which can be improved upon by enterprising investigative journalists in covering the crisis of Covid-19 and its many-sided impacts:

1. Oversight on the role of parliaments and local government

Journalists should play an oversight role in checking whether or not parliaments and other local government structures are doing what they should be doing (e.g. is Parliament holding the executive accountable for its actions and how is it doing this? In Botswana, for example, the government recently had to recall Parliament from recess to approve a six-month emergency imposed by the government there, so that the emergency rule was in line with the prescripts of the national legislation). Who checks on the actions of local government officials in terms of their actions, including selecting people who may benefit from government food handouts? Is this distribution being done fairly and equitably, and what metrics or criteria are used by officials to determine who has to benefit or not? What avenues are there for those people who feel unfairly neglected to voice their concerns?

2. Oversight on role of the executive government’s planning and budget plans for Covid-19

Journalists should check whether emergency laws and lockdowns are in line with national laws, focusing in particular on checking that the basic rights of ordinary people are not trampled upon. How are these emergency rules enabling or dis-enabling the imposition and implementation of national lockdowns?

Do national police and defence organs enforcing the lockdowns operate within the law or not; who monitors their actions and where can the public report complaints of excessive use of force or abuse so that these are investigated fully? Is there a police or military ombuds-person for this purpose, what are their contact details and what action can they take against military/police offenders? Who protects the whistle-blowers and how?

Has the government announced an emergency budget to tackle Covid-19; how will this money be used, by whom and when and using what criteria; are the poor people going to be looked after during the pandemic and how will this be done; is the food distribution and testing for the virus evenly distributed among various provinces of countries; are the results of the government’s tests for the virus being regularly communicated to the public in a transparent and public manner; is government accepting donor funds to help in the virus’ fight and how will these funds be disbursed, by whom and under what circumstances, and who can apply to access them and how, etc.?

Is the government communicating its messages clearly and consistently so that the public is not left confused or with mixed messages (here, you may recall US President Donald Trump’s political antics, where he repeatedly contradicted his own medical experts when addressing the American people on the Covid-19 during his daily media briefings. He even suggested that the ‘social distancing’ clampdown imposed by most US states should be removed by Easter!) It is this sort of messaging that creates problems in how to tackle the coronavirus in a cooperative, coordinated and concerted effort.

Does the government show transparency in how it is using test results and statistical models on the rates of infections and death to base its policy of fighting this virus, or is it purely thumb-suck? The message must be repeated loudly and clearly in all reporting, quoting medical experts, that science should lead and inform any measures that are meant to either tighten or ease these lockdowns, and not political grandstanding by politicians – some of whom are using the crisis to seek re-election.

3. Oversight on profiteering during the Covid-19 crisis

It is an oxymoron to state that in every crisis there are always people who stand to benefit from it. It is therefore up to the investigative journalists to check on who is or might be profiteering from the Covid-19 crisis in terms of procurement of goods and services, for example. Or, in terms of creating artificial shortages of desperately needed medical or food supplies so as to profit from any such shortages.

The journalists should regularly check with consumer agencies and anti-competition bodies on the above, along with speaking to ordinary people, who are the most affected and are likely to be valuable sources of important information. Journalists are encouraged to seek and obtain regular updates from the government on progress with sourcing of critical medical supplies, including the costs associated with sourcing such material and the quantities involved so that associated costs can be tracked.

4. Oversight on tracking of Covid-19 patients using mobile geo-location systems

Some governments are increasingly using mobile phones and systems to track the location of Covid-19 patients. Serious questions have been rightly raised by human rights agencies and digital media scholars on whether governments will only access information and data that relates to this disease, and not spy on people and their normal ordinary lives and trample on their privacy rights.

A week ago Google and Apple teamed up to roll out a new mobile tracking system which both companies claim does not violate individual privacy, but is this true and who can still trust these global tech companies? Have journalists checked these claims?

Let us not forget Facebook’s 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal. Journalists need to check, double-check and triple-check these claims by speaking to world experts on such systems, who these days can be interviewed from anywhere in the world using simple email or other online tools.

5. Oversight on the impact of Covid-19 on national economies and people’s livelihoods

Journalists are encouraged to probe the devastating impact of Covid-19 on the economies of their countries and on the livelihoods of citizens, especially of the poor.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has just warned that the world economy will suffer its worst economic decline in a century in 2020, with global Gross Domestic Product tumbling by an unprecedented three percent, almost akin to the impact of the 1930s Great Depression.

IMF economists estimate that global output of US$9 trillion will be lost this year and next year, which is equal to the combined economies of Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, and Japan.

The New Zealand Herald quotes Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s chief economist as saying:

“As countries implement necessary quarantines and social distancing practices to contain the pandemic, the world has been put in a Great Lockdown.

“The magnitude and speed of collapse in (economic) activity that has followed is unlike anything experienced in our lifetimes. This is a crisis like no other. This makes the Great Lockdown the worst recession since the Great Depression, and far worse than the global financial crisis (of 2007-2008).”

In this environment, most developing countries will witness a great number of people slipping into poverty, which will take years to address. South Africa, for example, was already in a recession before the advent of Covid-19.

For the investigative journalists, it will be essential for them to investigate how are the poor are being cushioned by governments from the worst social and economic effects of Covid-19, and whether these state-led intervention programmes are successful or not, and why? Also, investigations could seek causal factors, such as prior investment (or lack of) into key public services and social protections; loss of public funds through corruption; and the mounting debt burden on poor countries in the region. How have these factors contributed to weakening public services to the extent that they fail people when they most need them?

To paraphrase Trump, the cure should not be worse than the problem (the disease) itself. In other words, it would be a tragedy if more poor people were to die from hunger than from Covid-19.

It is therefore the responsibility of journalists to not just surface this human suffering and how it is being ameliorated by governments and its many social and business partners, but to put human faces behind the many statistics of the sick and of the dying to try to precipitate a united and decisive global response to this disease.

Conclusion

In all of the above reporting scenarios, it is absolutely important that investigative journalists do everything and anything to protect their sources of information. This is the foundation and hallmark of all credible and trusted journalism. We at HA expect nothing less, especially in this time of unprecedented peril for humanity.

Journalists must stand up and be counted as having made a positive difference to the human race during one of its darkest and dangerous health threats in modern history.

By Francis Mdlongwa, Director of Highway Africa (HA) and of Rhodes University’s Sol Plaatje Institute for Media Leadership.